Timing

This page describes various issues related to timing, and provides benchmark results and tips for testing your own system. If you experience problems with timing, please take the time to read this page. Many issues are resolved by taking into account things such as stimulus preparation and the properties of your monitor.

Is OpenSesame capable of millisecond precision timing?

The short answer is: yes. The long answer is the rest of this page.

Important considerations for time-critical experiments

Check your timing!

OpenSesame allows you to control your experimental timing very accurately. But this does not guarantee accurate timing in every specific experiment! For any number of reasons, many of which described on this page, you may experience issues with timing. Therefore, in time-critical experiments you should always check whether the timing in your experiment is as intended. The easiest way to do this is by checking the display timestamps reported by OpenSesame.

Every sketchpad item has a variable called time_[sketchpad name] that contains the timestamp of the last time that the sketchpad was shown. So, for example, if you want the sketchpad target to be shown for 100 ms, followed by the sketchpad mask, you should verify that time_mask - time_target is indeed 100. When using Python inline code, you can make use of the fact that canvas.show() returns the display timestamp.

Understanding your monitor

Computer monitors refresh periodically. For example, if the refresh rate of your monitor is 100 Hz, the display is refreshed every 10 ms (1000 ms / 100 Hz). This means that a visual stimulus is always presented for a duration that is a multiple of 10 ms, and you will not be able to present a stimulus for, say, 5 or 37 ms. The most common refresh rate is 60 Hz (= 16.67 ms refresh cycle), although monitors with much higher refresh rates are sometimes used for experimental systems.

In Video 1 you can see what a monitor refresh looks like in slow motion. On CRT monitors (i.e. non-flatscreen, center) the refresh is a single pixel that traces across the monitor from left to right and top to bottom. Therefore, only one pixel is lighted at a time, which is why CRT monitors flicker slightly. On LCD or TFT monitors (flatscreen, left and right) the refresh is a 'flood fill' from top to bottom. Therefore, LCD and TFT monitors do not flicker. (Unless you present a flickering stimulus, of course.)

If a new stimulus display is presented while the refresh cycle is halfway, you will observe 'tearing'. That is, the upper half of the monitor will show the old display, while the lower part will show the new display. This is generally considered undesirable, and therefore a new display should be presented at the exact moment that the refresh cycle starts from the top. This is called 'synchronization to the vertical refresh' or simply 'v-sync'. When v-sync is enabled, tearing is no longer visible, because the tear coincides with the upper edge of the monitor. However, and this appears to be a little recognized fact, v-sync does not change anything about the fact that the monitor will always, for some time, show both the old and the new display.

Another important concept is that of 'blocking on the vertical retrace' or the 'blocking flip'. Usually, when you send a command to show a new display, the computer will accept this command right away and put the to-be-shown display in a queue. However, the display may not actually appear on the monitor for some time, typically until the start of the next refresh cycle (assuming that v-sync is enabled). Therefore, you don't know exactly when the display has appeared, because your timestamp reflects the moment that the display was queued, rather than the moment that it was presented. To get around this issue, you can use a so-called 'blocking flip'. This basically means that when you send a command to show a new display, the computer will freeze until the display actually appears. This allows you to get very accurate display timestamps, at the cost of a significant performance hit due to the computer being frozen for much of the time. But for the purpose of experiments, a blocking flip is generally considered the optimal strategy.

Finally, LCD monitors may suffer from 'input lag'. This means that there is an additional and sometimes variable delay between the moment that the computer 'thinks' that a display appears, and the moment that the display actually appears. This delay results from various forms of digital processing that are performed by the monitor, such as color correction or image smoothing. As far as I know, input lag is not something that can be resolved programmatically, and you should avoid monitors with significant input lag for time-critical experiments.

For a related discussion, see:

Making the refresh deadline

Imagine that you arrive at a train station at 10:30. Your train leaves at 11:00, which gives you exactly 30 minutes to get a cup of coffee. However, when you have coffee for exactly 30 minutes, you will arrive back at the track just in time to see your train depart and you will have to wait for the next train. Therefore, if you have 30 minutes waiting time, you should have a coffee for slightly less than 30 minutes. 25 minutes, for example.

The situation is analogous when specifying intervals for visual-stimulus presentation. Let's say that you have a 100 Hz monitor (so 1 refresh every 10 ms) and want to present a target stimulus for 100 ms, followed by a mask. Your first inclination might be to specify an interval of 100 ms between the target and the mask, because that's after all what you want. However, specifying an interval of exactly 100 ms will likely cause the mask to 'miss the refresh deadline', and the mask will be presented only on the next refresh cycle, which is 10 ms later (assuming that v-sync is enabled). So if you specify an interval of 100 ms, you will in most cases end up with an interval of 110 ms! The solution is simple: You should specify an interval that is slightly shorter than what you are aiming for, such as 95 ms. Don't worry about the interval being too short, because on a 100 Hz monitor the interval between two stimulus displays is necessarily a multiple of 10 ms. Therefore, 95 ms will become 100 ms (10 frames), 1 ms will become 10 ms (1 frame), etc. Phrased differently, intervals will be rounded up (but never rounded down!) to the nearest interval that is consistent with your monitor's refresh rate.

Disabling desktop effects

Many modern operating systems make use of graphical desktop effects. These provide, for example, the transparency effects on Windows 7, the wobbly windows on Linux, or the smooth window minimization and maximization effects that you see on many systems. Although the software that underlies these effects differs from system to system, they generally form an additional layer between your application and the display. This additional layer may prevent OpenSesame from synchronizing to the vertical refresh and/ or from implementing a blocking flip, as described under [Understanding your monitor].

Note that although desktop effects may cause problems, they usually don't. This appears to vary from system to system and from video card to video card. Nevertheless, to be safe, I recommend disabling desktop effects on systems that are used for experimental testing.

Some tips regarding desktop effects for the various operating systems:

- Under Windows XP there are no desktop effects at all.

- Under Windows 7 desktop effects can be disabled by selecting any of the themes listed under 'Basic and High Contrast Themes' in the 'Personalization' section.

- Under Ubuntu you can use Unity 2D to disable desktop effects.

- Under Linux distributions using Gnome 3 there is apparently no way to disable desktop effects.

- Under Linux distributions using KDE you can disable desktop effects in the 'Desktop Effects' section of the System Settings.

- Under Mac OS there is apparently no way to disable desktop effects.

Taking into account stimulus-preparation time/ the prepare-run structure

If you care about accurate timing during visual-stimulus presentation, you should prepare your stimuli in advance. That way, you will not get any unpredictable delays due to stimulus preparation during the time-critical parts of your experiment.

Let's first consider a script (you can paste this into an inline_script item) that includes stimulus-preparation time in the interval between canvas1 and canvas2 (Listing 1). The interval that is specified is 95 ms, so--taking into account the 'rounding up' rule described in [Making the refresh deadline]--you would expect an interval of 100 ms on my 60 Hz monitor. However, on my test system the script below results in an interval of 150 ms, which corresponds to 9 frames on a 60 Hz monitor. This is an unexpected delay of 50 ms, or 3 frames, due to the preparation of canvas2.

# Warning: This is an example of how you should *not*

# implement stimulus presentation in time-critical

# experiments.

from openexp.canvas import canvas

# Prepare canvas 1 and show it

canvas1 = canvas(exp)

canvas1.text('This is the first canvas')

t1 = canvas1.show()

# Sleep for 95 ms to get a 100 ms delay

self.sleep(95)

# Prepare canvas 2 and show it

canvas2 = canvas(exp)

canvas2.text('This is the second canvas')

t2 = canvas2.show()

# The actual delay will be more than 100 ms, because

# stimulus preparation time is included. This is bad!

print 'Actual delay: %s' % (t2-t1)

Now let's consider a simple variation of the script above (Listing 2). This time, we first prepare both canvas1 and canvas2 and only afterwards present them. On my test system, this results in a consistent 100 ms interval, just as it should!

# Prepare canvas 1 and 2

canvas1 = canvas(exp)

canvas1.text('This is the first canvas')

canvas2 = canvas(exp)

canvas2.text('This is the second canvas')

# Show canvas 1

t1 = canvas1.show()

# Sleep for 95 ms to get a 100 ms delay

self.sleep(95)

# Show canvas 2

t2 = canvas2.show()

# The actual delay will be 100 ms, because stimulus

# preparation time is not included. This is good!

print 'Actual delay: %s' % (t2-t1)

When using the graphical interface, the same considerations apply, but OpenSesame helps you by automatically handling most of the stimulus preparation in advance. However, you have to take into account that this preparation occurs at the level of sequence items, and not at the level of loop items. Practically speaking, this means that the timing within a sequence is not confounded by stimulus-preparation time. But the timing between sequences is.

To make this more concrete, let's consider the structure shown below (Figure 1). Suppose that the duration of the sketchpad item is set to 95 ms, thus aiming for a 100 ms duration, or 6 frames on a 60 Hz monitor. On my test system the actual duration is 133 ms, or 8 frames, because the timing is confounded by preparation of the sketchpad item, which occurs each time that that the sequence is executed. So this is an example of how you should not implement time-critical parts of your experiment.

Figure 1. An example of an experimental structure in which the timing between successive presentations of sketchpad is confounded by stimulus-preparation time. The sequence of events in this case is as follows: prepare sketchpad (2 frames), show sketchpad (6 frames), prepare sketchpad (2 frames), show sketchpad (6 frames), etc.

Now let's consider the structure shown below (Figure 2). Suppose that the duration of sketchpad1 is set to 95 ms, thus aiming for a 100 ms interval between sketchpad1 and sketchpad2. In this case, both items are shown as part of the same sequence and the timing will not be confounded by stimulus-preparation time. On my test system the actual interval between sketchpad1 and sketchpad2 is therefore indeed 100 ms, or 6 frames on a 60 Hz monitor.

Note that this only applies to the interval between sketchpad1 and sketchpad2, because they are executed in that order as part of the same sequence. The interval between sketchpad2 on run i and sketchpad1 on run i+1 is again confounded by stimulus-preparation time.

Figure 2. An example of an experimental structure in which the timing between the presentation of sketchpad1 and sketchpad2 is not confounded by stimulus-preparation time. The sequence of events in this case is as follows: prepare sketchpad1 (2 frames), prepare sketchpad2 (2 frames), show sketchpad1 (6 frames), show sketchpad2 (6 frames), prepare sketchpad1 (2 frames), prepare sketchpad2 (2 frames), show sketchpad1 (6 frames), show sketchpad2 (6 frames), etc.

For more information, see:

Differences between backends

OpenSesame is not tied to one specific way of controlling the display, system timer, etc. Therefore, OpenSesame per se does not have specific timing properties, because these depend on the backend that is used. The performance characteristics of the various backends are not perfectly correlated: It is possible that on some system the psycho backend works best, whereas on another system the xpyriment backend works best. Therefore, one of the great things about OpenSesame is that you can choose which backend works best for you!

In general, the xpyriment and psycho backends are preferable for time-critical experiments, because they use a blocking flip, as described in [Understanding your monitor]. On the other hand, the legacy backend is slightly more stable and also considerably faster when using forms.

Under normal circumstances the three current OpenSesame backends have the properties shown in Table 1.

| backend | V-sync | Blocking flip |

|---|---|---|

| legacy | yes | no |

| xpyriment | yes | yes |

| psycho | yes | yes |

Table 1. backend properties.

See also:

Benchmark results and tips for testing your own system

Checking whether v-sync is enabled

As described in [Understanding your monitor], the presentation of a new display should ideally coincide with the start of a new refresh cycle (i.e. 'v-sync'). You can test whether this is the case by presenting displays of different colors in rapid alternation. If v-sync is not enabled you will clearly observe horizontal lines running across the monitor (i.e. 'tearing'). To perform this test, run an experiment with the following script in an inline_script item (Listing 3):

from openexp.canvas import canvas

from openexp.keyboard import keyboard

# Create a blue and a yellow canvas

blue_canvas = canvas(exp, bgcolor='blue')

yellow_canvas = canvas(exp, bgcolor='yellow')

# Create a keyboard object

my_keyboard = keyboard(exp, timeout=0)

# Alternately present the blue and yellow canvas until

# a key is pressed.

while my_keyboard.get_key()[0] == None:

blue_canvas.show()

self.sleep(95)

yellow_canvas.show()

self.sleep(95)

Testing consistency of timing and timestamp accuracy

Timing is consistent when you can present visual stimuli over and over again with the same timing. Timestamps are accurate when they accurately reflect when visual stimuli appear on the monitor. The script below shows how you can check timing consistency and timestamp accuracy. This test can be performed both with and without an external photodiode, although the use of a photodiode provides extra verification.

To keep things simple, let's assume that your monitor is running at 100 Hz, which means that a single frame takes 10 ms. The script then presents a white canvas for 1 frame (10 ms). Next, the script presents a black canvas for 9 frames (90 ms). Note that we have specified a duration of 85, which is rounded up as explained under [Making the refresh deadline]. Therefore, we expect that the interval between the onsets of two consecutive white displays will be 10 frames or 100 ms (= 10 ms + 90 ms).

We can use two ways to verify whether the interval between two white displays is indeed 100 ms:

- Using the timestamps reported by OpenSesame. This is the easiest way and is generally accurate when the backend uses a blocking flip, as described in [Understanding your monitor].

- Using a photodiode that responds to the onsets of the white displays and logs the timestamps of these onsets to an external computer. This is the best way to verify the timing, because it does not rely on introspection of the software. Certain issues, such as TFT input lag, discussed in [Understanding your monitor], will come out only using external photodiode measurement.

# The numbers in this script assume a 100 Hz refresh rate! Adjust the numbers

# according to your monitor.

from openexp.canvas import canvas

import numpy as np

# The interval for the black canvas. This will be 'rounded up' to 90 ms, or 9

# frames.

interval = 85

# The number of presentation cycles to test.

N = 100

# Create a black and a white canvas.

white_canvas = canvas(exp, bgcolor='white')

black_canvas = canvas(exp, bgcolor='black')

# Create an array to store the timestamps for the white display.

a_white = np.empty(N)

# Loop through the presentation cycles.

for i in range(N):

# Present a white canvas for a single frame. I.e. do not wait at all after

# the presentation.

a_white[i] = white_canvas.show()

# Present a black canvas for 9 frames. I.e. wait for 85 ms after the

# presentation.

black_canvas.show()

self.sleep(interval)

# Write the timestamps of the white displays to a file.

np.savetxt('timestamps.txt', a_white)

# For convenience, summarize the intervals between the white displays and print

# this to the debug window.

d_white = a_white[1:]-a_white[:-1]

print 'M = %.2f, SD = %.2f' % (d_white.mean(), d_white.std())

I ran Listing 4 on Windows XP, using all three backends. I also recorded the onsets of the white displays using a photodiode connected to a second computer. The results are summarized in Table 2.

| backend | Session | Source | M (ms) | SD (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| xpyriment | 1.0000 | OpenSesame | 100.0000 | 0.6200 |

| Photodiode | 100.0100 | 0.0200 | ||

| 2.0000 | OpenSesame | 100.0100 | 0.7900 | |

| Photodiode | 100.0100 | 0.0200 | ||

| psycho | 1.0000 | OpenSesame | 100.0000 | 0.0100 |

| Photodiode | 100.0100 | 0.0200 | ||

| 2.0000 | OpenSesame | 100.0000 | 0.0100 | |

| Photodiode | 100.0100 | 0.0200 | ||

| legacy | 1.0000 | OpenSesame | 90.0000 | 0.5200 |

| Photodiode | 90.0000 | 0.0300 | ||

| 2.0000 | OpenSesame | 90.0000 | 0.4900 | |

| Photodiode | 90.0000 | 0.0200 |

Table 2. Benchmark results for Listing 4. Tested with Windows XP, HP Compaq dc7900, Intel Core 2 Quad Q9400 @ 2.66Ghz, 3GB, 21" ViewSonic P227f CRT. Each test was conducted twice (i.e. two sessions). The column Session corresponds to different test runs. The column Source indicates whether the measurements are from an external photiodiode, or based on OpenSesame's internal timestamps.

As you can see, the xpyriment and psycho backends consistently show a 100 ms interval. This is good and just as we would expect. However, the legacy backend shows a 90 ms interval. This discrepancy is due to the fact that the legacy backend does not use a blocking flip (see [Understanding your monitor]), which leads to some unpredictability in display timing. Note also that there is close agreement between the timestamps as recorded by the external photodiode and the timestamps reported by OpenSesame. This agreement demonstrates that OpenSesame's timestamps are reliable, although, again, they are slightly less reliable for the legacy backend due to the lack of a blocking-flip.

Checking for clock drift in high-resolution timers (Windows only)

Under Windows, there are two ways to obtain the system time. The Windows Performance Query Counter (QPC) API reportedly provides the highest accuracy. The CPU Time Stamp Counter (TSC), which relies on the number of clock ticks since the CPU started running, is somewhat less accurate. Of course, these two timers should be in sync with each other. A significant deviation between the QPC and TSC indicates a problem with your system's internal timer. Currently, the psycho and xpyriment backends makes use of the QPC. The legacy backends rely on the TSC.

Listing 5 determines a drift value that indicates how much the QPC and TSC diverge. This value should be very close to 1, meaning no divergence. Values higher than 1 indicate that the TSC runs faster than the QPC. You can run this script directly in a Python interpreter or by pasting it in an inline_script item (in which case you may need to comment out the references to matplotlib, because this library is not included in all OpenSesame packages).

from time import time as getTickTime, sleep as tickSleep

from ctypes import byref, c_int64, windll

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

# The number of samples to get

N = 1000

# The sleep period between samples (in sec.)

sleep = .1

def getQPCTime():

"""

Uses the Windows QueryPerformanceFrequency API to get the system time. This

implements the high-resolution timer as used for example by PsychoPy and

PsychoPhysics toolbox.

Returns:

A timestamp (float)

"""

_winQPC(byref(_fcounter))

return _fcounter.value/_qpfreq

# Complicated ctypes magic to initialize the Windows QueryPerformanceFrequency

# API. Adapted from the psychopy.core.clock source code.

_fcounter = c_int64()

_qpfreq = c_int64()

windll.Kernel32.QueryPerformanceFrequency(byref(_qpfreq))

_qpfreq = float(_qpfreq.value)

_winQPC = windll.Kernel32.QueryPerformanceCounter

# Create empty numpy arrays to store the results

aQPC = np.empty(N, dtype=float)

aTick = np.empty(N, dtype=float)

aDrift = np.empty(N, dtype=float)

# Wait for a minute to allow the Python interpreter to settle down.

tickSleep(1)

# Get the onset timestamps for the timers.

onsetQPCTime, onsetTickTime = getQPCTime(), getTickTime()

# Repeatedly check both timers

print "QPC\ttick\tdrift"

for i in range(N):

# Get the QPC time and the tickTime

QPCTime = getQPCTime()

tickTime = getTickTime()

# Subtract the onset time

QPCTime -= onsetQPCTime

tickTime -= onsetTickTime

# Determine the drift, such that > 1 is a relatively slowed QPC timer.

drift = tickTime / QPCTime

# Sleep to avoid too many samples.

tickSleep(sleep)

# Print output

print "%.4f\t%.4f\t%.4f" % (QPCTime, tickTime, drift)

# Save the results in the arrays

aQPC[i] = QPCTime

aTick[i] = tickTime

aDrift[i] = drift

# The first drift sample should be discarded

aDrift = aDrift[1:]

# Create a nice plot of the results

plt.figure(figsize=(6.4, 3.2))

plt.rc('font', size=10)

plt.subplots_adjust(wspace=.4, bottom=.2)

plt.subplot(121)

plt.plot(aQPC, color='#f57900', label='QPC timer')

plt.plot(aTick, color='#3465a4', label='Tick timer')

plt.xlabel('Sample')

plt.ylabel('Timestamp (sec)')

plt.legend(loc='upper left')

plt.subplot(122)

plt.plot(aDrift, color='#3465a4', label='Timer drift')

plt.axhline(1, linestyle='--', color='black')

plt.xlabel('Sample')

plt.ylabel('tick / QPC')

plt.savefig('systemTimerDrift.png')

plt.savefig('systemTimerDrift.svg')

plt.show()

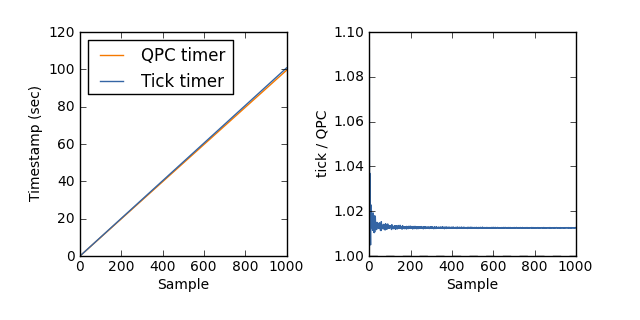

I tested this script on two systems. On the first system, shown in Figure 3, there was a slight drift of about 1.2%. This drift was consistently present within this particularly session, but not across different sessions. On many other occasions the same system did not exhibit any drift at all. The reason why, on this system, a slight clock drift comes and goes is unclear.

Figure 3. Windows XP, HP Compaq dc7900, Intel Core 2 Quad Q9400 @ 2.66Ghz, 3GB

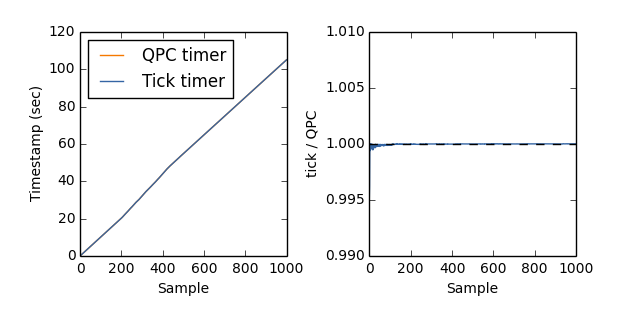

The second system, shown in Figure 4, showed no drift at all, at least not during this particular session.

Figure 4. Windows 7, Acer Aspire V5-171, Intel Core I3-2365M @ 1.4Ghz, 6GB

This issue is described in more detail on the Psychophysics Toolbox website.

- http://docs.psychtoolbox.org/GetSecsTest

- http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ee417693%28VS.85%29.aspx

Expyriment benchmarks and test suite

A very nice set of benchmarks is available on the Expyriment website. This information is applicable to OpenSesame experiments using the xpyriment backend.

Expyriment includes a very useful test suite. You can launch this test suite by running the test_suite.opensesame example experiment, or by adding a simple inline_script to your experiment with the following lines of code (Listing 6):

import expyriment

expyriment.control.run_test_suite()

For more information, please visit:

PsychoPy benchmarks and timing-related information

Some information about timing is available on the PsychoPy documentation site. This information is applicable to OpenSesame experiments using the psycho backend.